The Arch of Allegiance: An Examination of Loyalty Systems in Beowulf and The Romance of Tristan

The Arch of Allegiance: An Examination of Loyalty Systems in Beowulf and The Romance of Tristan

By R. S. Forste

Beowulf is a good poem, as its unknown author might say. It is also a more or less complete poem. Although it appears that there are a few holes in the manuscript, the lost pieces of Beowulf do not seem to be essential to the integrity of the whole because what remains stands alone without support from other texts (provided one has a knowledge of Old English or a translation.)

On the other hand, Beroul’s The Romance of Tristan survives in a far more fragmentary state. In order to make it comprehensible, it is necessary to borrow and insert extensive passages from other sources. So, unlike Beowulf, The Romance of Tristan is not a complete poem. Therefore, a comparison of these two texts is problematic, but not impossible. It is somewhat like comparing a crumbling stone arch to a remnant of moth-eaten embroidery: it can certainly be done, it might even be fun, but the main basis for a comparison of these two objects is that they are both old.

Interestingly, these metaphors also provide a convenient way of contrasting the allegiance systems revealed in these two texts. The stone arch serves to explicate the concept of service to the lord as the ideal of Beowulf, while the scrap of embroidery is just as appropriate a symbol of service to the lady as exemplified in The Romance of Tristan. How is Beowulf like a stone arch? Both are heavy and solid, perhaps “masculine.” Moreover, the structure of a stone arch provides a good analogy for the hierarchical structure of the communities in which the people of Beowulf live. At the top of the arch is the keystone, which can be compared to a lord like Hrothgar. He is at the top, but only because he is held up by his thanes , which can be represented by the other stones in the arch.

Similarly, if Hrothgar, or the keystone, crumbles or is removed, the entire structure, stones, thanes and all, comes tumbling down. The communities of Beowulf’s world are interdependent structures. Visualizing one as a stone arch helps to vividly illustrate the importance of loyalty to the lord to this structure. The disastrous results of thanes failing to support their lord are obvious when conceptualized in this way, as are the equally disastrous results of a weak lord.

Likewise, those all-important gifts, the hoards of gold, weapons and armor, the mead halls and perhaps the “peace-weaver” women can be viewed as the mortar which helped the structure stick together. On the first page we are told that it is “by splendid bestowals” that a leader can expect to win the loyalty of his “chosen men” and prosper (49). From then on, the importance of treasure in this world is continually and emphatically underscored. The poet sings of “bright gold and silver, gems from far lands … weapons of battle, swords and mail-shirts,” (51) “golden war-standard … with plated ornament … a jewel-encrusted long sword,” (107) and on and on and on.

However, these gifts do not ever seem to represent actual gain to the recipients. From the treasure which accompanies Scyld Scefing on his arrival, to the gifts bestowed upon Beowulf by Hrothgar which are in turn bestowed upon Hygelac, to the dragon’s hoard with which Beowulf is buried — “gold in the ground, .. as useless to men as it was before” — all gifts either return to their source or are given to someone else. (243) These “splendid bestowals” do not enrich people, they maintain equilibrium between them. The gifts had a greater ceremonial than intrinsic value.

Gift giving is more a ritual than an economic activity in Beowulf’s world. Yet, no matter how lavish the gifts, no matter how loyal the thanes, no matter how strong the lord, all structures in this world are temporary. They are built with the moment of their collapse forever in mind, just as the arrival of Scyld Scefing cannot be mentioned without including an allusion to his departure and the construction of Heorot cannot be described without also referring to its destruction. There is some logic to this attitude. If, as we have supposed, the gifts of treasure and arms, the mead-hall gatherings and the strategic marriages were the mortar gluing these stones to one another, then potentially destructive forces were built right in to these structures.

If Beowulf is a reasonably accurate portrayal of the thanes’ and lord’s way of life, then we can conclude that far more time was devoted to war than to mining gold, metalworking or courting ladies (although perhaps almost as much time was spent drinking mead as fighting.) Where and how, then, were they to obtain the tremendous quantities of gold and armor their lifestyle seems to have demanded?

The most likely way seems to have been to attack another group and take their hoard. There is some indication of this in the first few lines of the poem: “Often Scyld Scefing seized mead benches from enemy troops” (49). Similarly, since the warriors of Heorot display no aptitude for winning the favor of ladies through their polished manners, it is likely that they supplied their needs here through war also. Clearly, if a culture operates by building structures out of materials obtained from the destruction of other structures, no structure will stand for very long. The mere act of building invites demolition. Hence, the obsession of this culture with the ephemeral quality of everything.

On the other hand, The Romance of Tristan may be seen as being as light, fluttery and “feminine” as a delicate and colorful embroidered handkerchief, a gift which a lady might give to a knight in her service. Moreover, the loyalties and intentions of Mark, and to a lesser extent, his nephew Tristan, are blown about as easily as a handkerchief, or “a long fair hair” floating from the beak of a swallow.

While death and destruction are always kept in mind by the author of Beowulf, Beroul has little interest in such dismal topics. He is far more interested in sex and deception. The arch of Beowulf’s world still stands, but it is a moss-covered ruin. In some ways, Tristan is still part of this structure, but it is as if the mortar which should be bonding him to his lord is missing.

If we continue to maintain that gifts are this mortar, then perhaps it may be concluded that the mortar is missing, for Tristan’s lord, Mark, is never seen bestowing either gold or women on his most able servant. It is true that Mark gives his sister Blanchefleur to Tristan’s father, but we read nothing of Mark rewarding Blanchfleur’s son. This is strange when one considers the fact that Mark gives Yseut away twice to people (the harper and the leper) who have rendered him little or no service and from whom he cannot reasonably expect loyalty.

Furthermore, there is also evidence that Mark is stingy toward those to whom he owes loyalty. It is because he has failed to pay his tribute to the King of Ireland that he is attacked by Morholt, leading to Tristan’s nearly fatal wound and his meeting with Yseut. Mark is more a keyjellyfish than a keystone. Hrothgar, and later Beowulf, are weak and pathetic only because they have grown old and cannot fight as well, but they seem to retain their judgment and ability to fulfill all the other functions of a lord. Mark, on the other hand, never seems to posses any judgment nor willingness nor ability to fulfill any of the functions of a lord.

It is the absence of gift giving in The Romance of Tristan that helps to make its role as mortar binding thane to lord even clearer. Gifts fixed loyalty not merely by evoking gratitude, but by fostering dependence. This is evident in the passage in which Mark banishes Tristan at his barons’ insistence, but tries in his typical way to serve all sides by offering Tristan “whatever he wanted… he offered him gold and silver and rich clothing.” (112) It is revealing that Mark makes this offer not to reward Tristan for Tristan’s good behavior but to compensate Tristan for Mark’s bad behavior. Yet, it is Mark’s past failure to give Tristan his due that enables Tristan to haughtily spurn this probably insincere offer: “King of Cornwall, I will never take a farthing from you.” (112) It is difficult to imagine any of the warriors of Beowulf uttering this sentence. His time in the wilderness has taught Tristan just how easily he can live without Mark’s feeble patronage.

However, as stated before, the ceremonial role of gift giving seems to have been far more important than its economic role. Gifts represented loyalty more than wealth. Mark’s failure to make “splendid bestowals” upon Tristan is more an indication of his unfaithfulness to Tristan than his miserliness. This is seen in the fact that his barons, Frocin or nearly anybody who happens to be speaking to him are able to influence him against Tristan.

Treasure also seems to be equated with words, as we see when Beowulf is described as having “unlocked his word hoard” (63). Moreover, the act of speaking in Beowulf seems to be regarded as something very momentous and serious. Over and over, the poet announces “Hrothgar spoke” or “Beowulf spoke” as if this really means something. Deceit is not unheard of in Beowulf’s world, since, as the coast-guard points out, there is a “distinction between words and deeds” (65) yet it is clearly not considered a virtue. There may be conflicting versions of the story of Beowulf’s swimming contest with Breca, but the reader is not likely to doubt that Beowulf’s version is, as he says, “the true story” (81). People may lie, but heroes do not.

While the words of Beowulf are as weighty and unyielding from the truth as stone, words in Tristan are used cleverly, like an embroidered hanky draped artfully over the damaging truth, diverting Mark’s flighty attention with its bright colors and butterfly-like movements. There seems to be no question that Beroul regards Tristan as a hero, yet he sees no need to apologize for or even explain the blatant deceptions in which Tristan and Yseut engage. On the contrary, he seems to imply that their behavior is virtuous, even divinely sanctioned. “God let me speak first,” Yseut tells Brangain in recounting her successful attempt to mislead Mark about her relationship with Tristan and Brangain does not hesitate to agree that “God has really worked a miracle for you” in giving Yseut such a great opportunity to lie, adding that God is “a true father, and he will not harm those who are loyal and good.” (54-55).

It would seem that Beroul and Beowulf define the terms “loyal and good” very differently. Beowulf is judged as being “loyal and good” in relation to his lord and his men, while Tristan and Yseut are judged as being “loyal and good” in relation to one another. Even so, I feel that there is some question about whether Tristan was as “loyal and good” to Yseut as he might have been. Tristan ultimately seems to be less a story of service to a lady than a story of the conflict between service to a lady and a lord. I am tempted to think that Tristan’s doom was more the result of genetic tendencies from his mother than the magic potion from Yseut’s mother. Like Mark, his mother’s brother, he wobbles back and forth, unable to fully break off his loyalty to Mark.

If Mark is to be found at fault for lightly handing over Yseut to the harper and the leper, then how can we excuse Tristan for repeatedly handing her back over to Mark? Tristan may love Yseut, but something still binds him to Mark, and since the mortar used by Beowulf has been ruled out, I suspect it may be the fact that he and Mark are cut from the same cloth.

Works Cited:

Beroul. The Romance of Tristan. Trans. Alan S. Fedrick. London: Penguin, 1970.

Chickering, Howell D., Jr., trans. Beowulf : a Dual-language Edition. New York: Anchor, 1977.

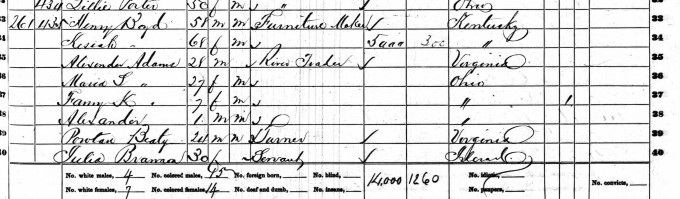

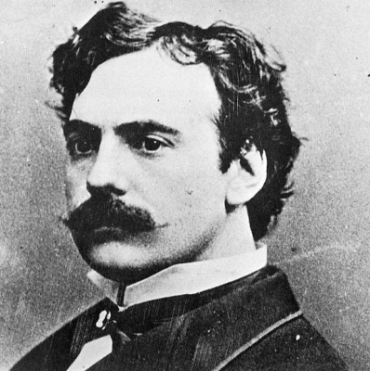

Most sources state that Beaty’s parents are unknown, but I have located a copy of his death certificate which lists his mother as A. Leigh. We know that Beaty named his first-born son Albert Lee Beaty. Also, the 1900 census shows a sister named Ellen Lee and a niece named Carrie Lee living in his household. These facts provide more evidence for Leigh/Lee as a family surname.

Most sources state that Beaty’s parents are unknown, but I have located a copy of his death certificate which lists his mother as A. Leigh. We know that Beaty named his first-born son Albert Lee Beaty. Also, the 1900 census shows a sister named Ellen Lee and a niece named Carrie Lee living in his household. These facts provide more evidence for Leigh/Lee as a family surname.